The Role of Wanting and Willing in Creating Consent

Not every authentic yes comes from desire.

When we talk about consent, most people picture a simple “yes” or “no” in response to someone asking to do something to you, or with you. You’re either a yes because you want that same thing, or you’re a no. But in embodied consent work, consent is far more nuanced, relational, and collaborative.

Most of the time, when we want to do something with another person, we use everyday language shaped by social niceties and cultural habits. These ways of communicating often have an indirect quality to them as we try to be nice and avoid offence or rejection.

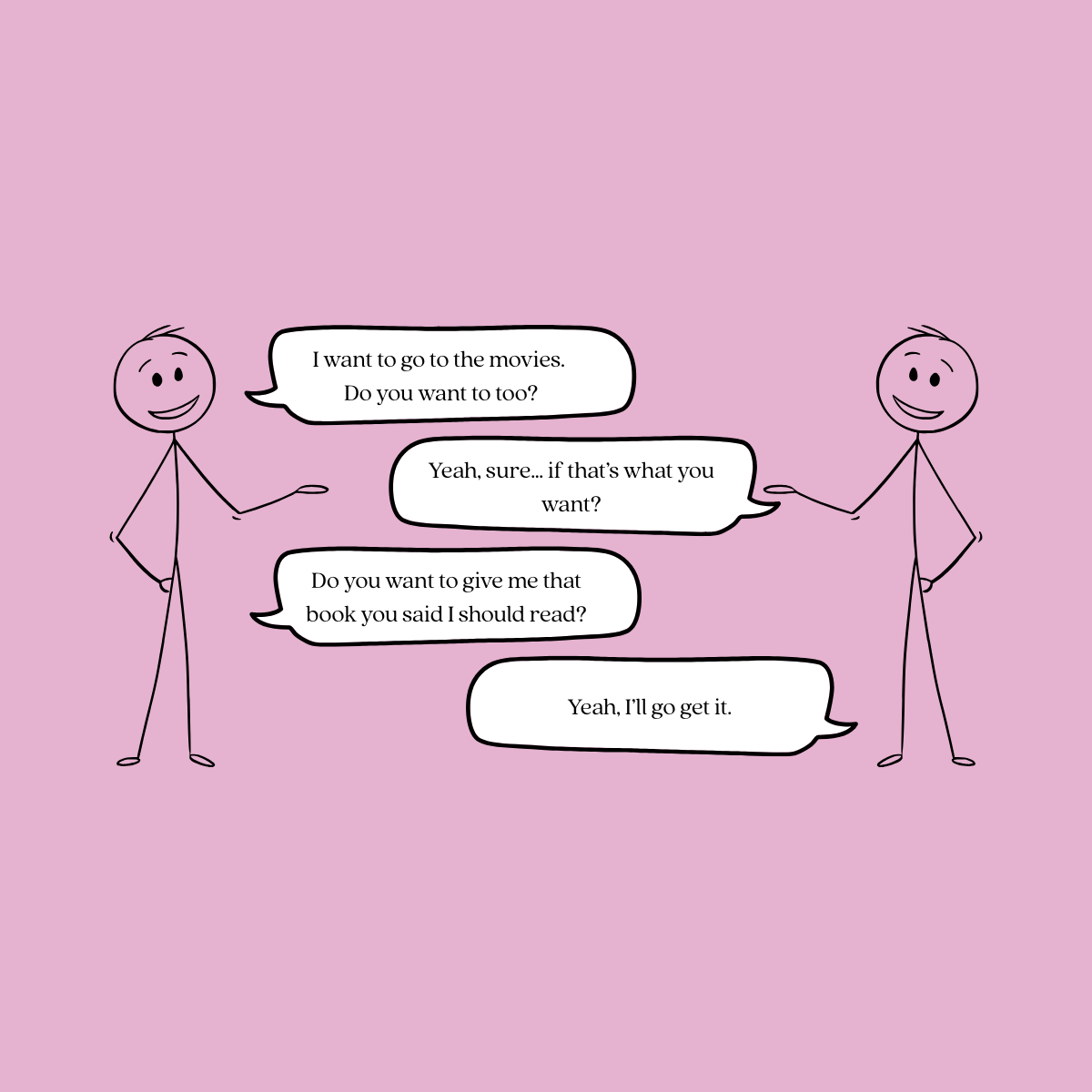

Consider these familiar interactions. Imagine both people are adults, close friends or lovers, speaking in a friendly, neutral tone, with no coercion or power imbalance.

On the surface, this looks like effective communication. Something is asked for, something is agreed to.

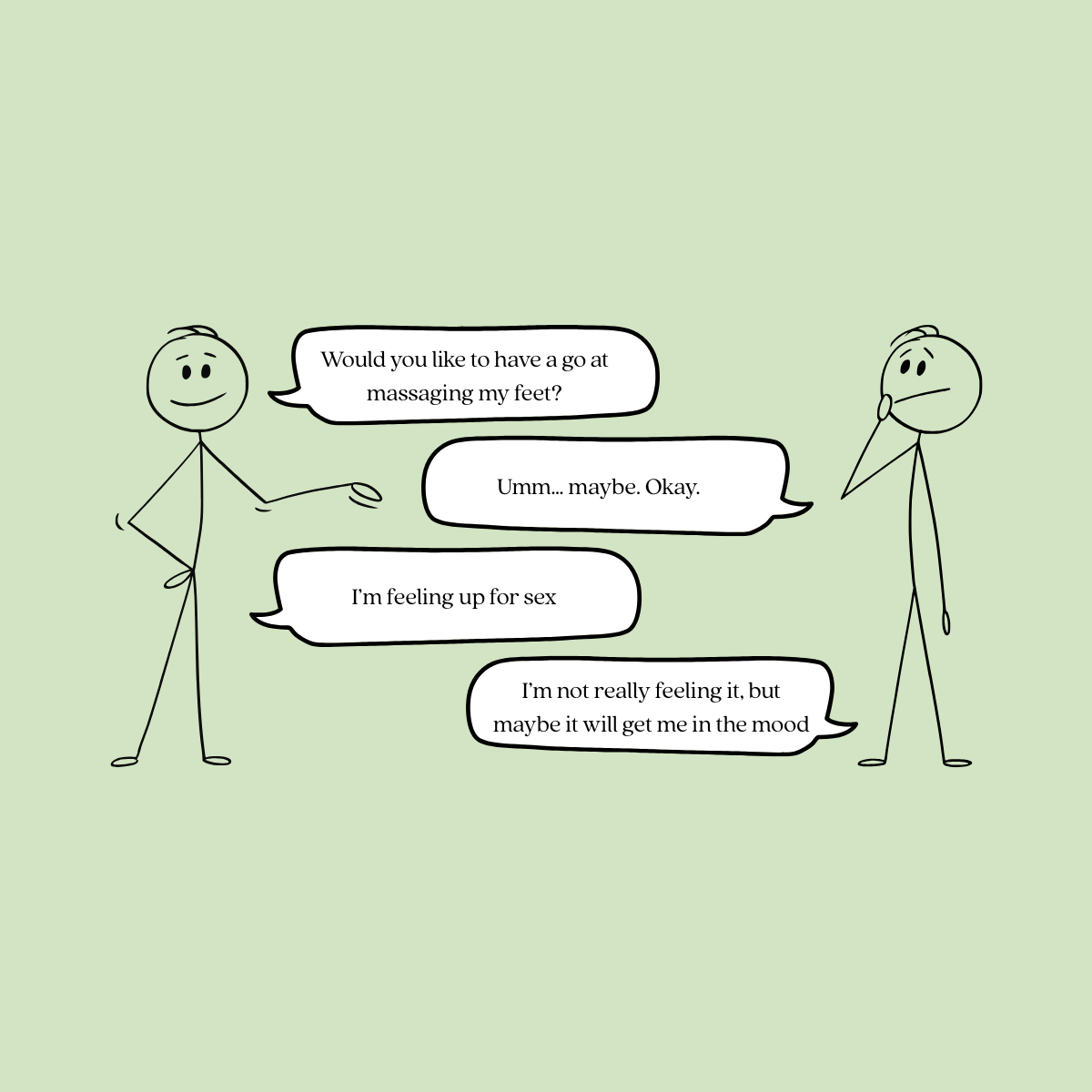

Even in slightly more vulnerable scenarios, consent can still appear to be present:

In each of these examples, one persons asks for something. The other person responds with what we might call a “yes”. Legally, socially, and culturally, this often counts as consent and many of us get by just fine using this style of communication most of the time. I’ve said these things. You probably have too.

And yet, something important can often be missing.

What’s Happening Beneath the ‘Yes’

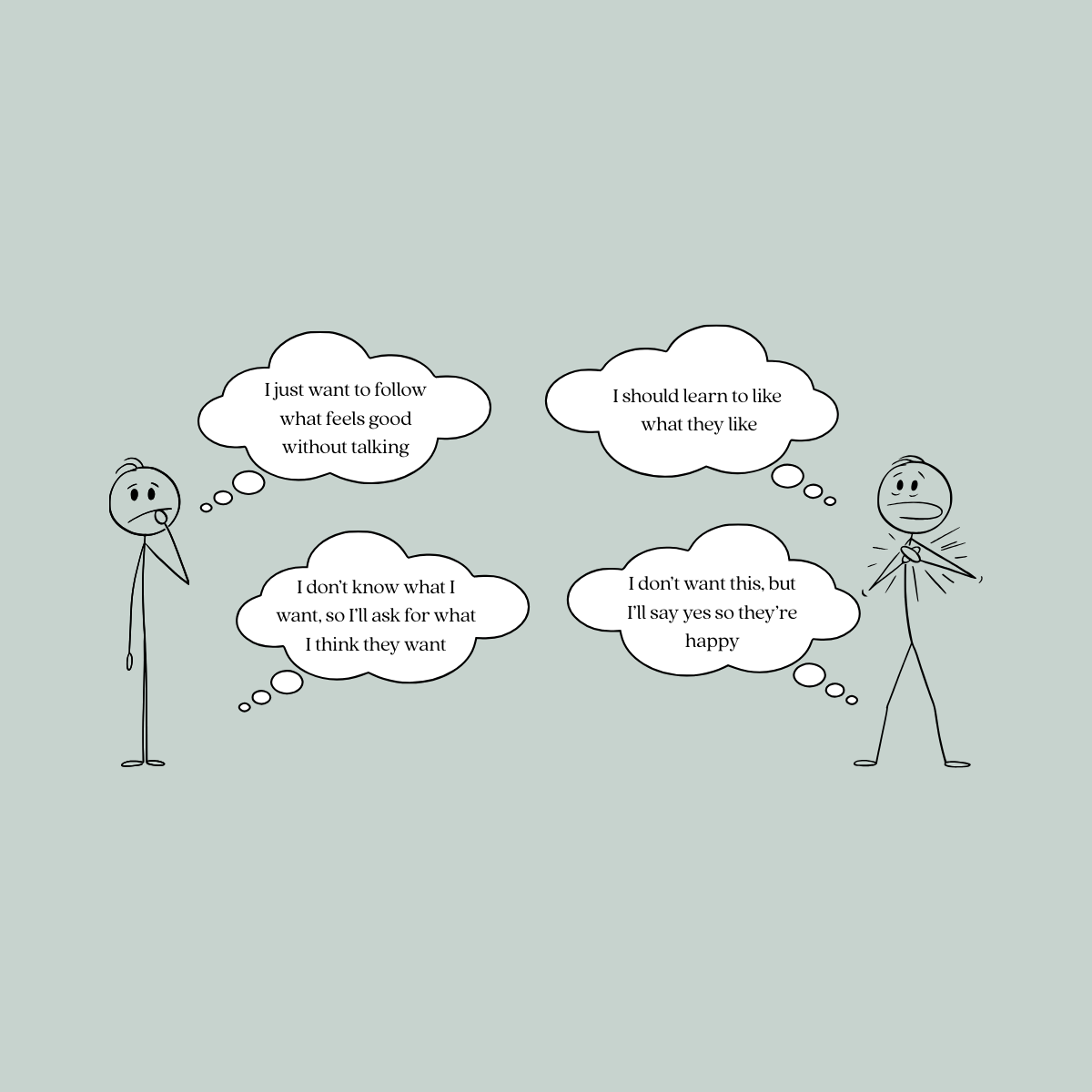

Even between loving, equal partners, there is a lot happening internally before, during, and after consent conversations. Both people may be experiencing multiple sensations, emotions, thoughts, and impulses often without much awareness or language for them.

These internal experiences can quickly turn into familiar patterns of thought:

Whether we are aware of them or not, these internal processes strongly influence our choices. And while consent may technically be “given” when someone says yes, that doesn’t mean the experience feels good, nourishing, or is truly consensual for everyone involved.

We are complex beings.

Is aiming only for the yes really serving us?

Wanting and Willing: Same or Different?

Consent researchers have spent decades trying to understand what consent is actually made of. Two terms that appear again and again are wantedness and willingness. Yet there is still no shared agreement about what they mean, or whether they are the same thing or different.

In everyday language, want and willing are often used interchangeably. Both usually signal a “yes, I’m up for this”. Some versions of consent frame consent as something that happens when two people both want the same thing or show willingness for it.

We both want this or we’re both willing to do this.

This model works sometimes but it doesn’t explain many real-life experiences such as where we agree to do things not because we want it for ourselves but for other reasons.

Can these scenarios still be ethically sound if one person doesn’t want it?

How the Wheel of Consent Clarifies the Difference

The Wheel of Consent offers a powerful distinction: wanting and willing are not the same thing.

They are distinct yet interrelated skills that support people to create consent together; framing interaction as an ongoing process of giving and receiving.

Wanting: Receiving What Is for You

Wanting is about your desire.

It is for you.

A want is something you notice, trust, and value inside yourself. It is a pull toward an experience because of how it will feel for you. The thing you want may involve another person, an action, or an object, but the desire lives in your body.

When your want involves another person, you must make a request; clear and specific. Making a request makes space for choice for the other person.

It’s respectful and forms part of your responsibility as a co-creator of consent.

Asking for what we want can feel vulnerable. Many of us have developed subtle and clever ways to avoid asking directly because we fear feeling things like rejection, judgment, disappointment, or unworthiness.

This can then show up as:

Touching someone without asking

Hinting instead of making a direct request

Over-giving with the hope they will reciprocate instead of naming desire

And many, many more.

Wanting is about receiving. It’s about something arriving as a gift for you. The gift could arrive through your action or the other person’s action but it is still for you.

When it arrives, you feel it on the inside as a positive experience.

Willing: Giving a Gift Within Your Limits

Willingness is different.

Willingness is a yes to giving a gift offered within your limits, for the other person. It is about doing or allowing something to happen that meets their want and desire.

When you are willing, the experience is not about what you want. Giving requires you to set aside your desires and instead pay attention to your limits: your capacity, your time, your energy, your comfort. This forms part of your responsibility in co-creating consent.

You might be willing:

for five minutes but not an hour

with this person but not that person

doing it one way but not another

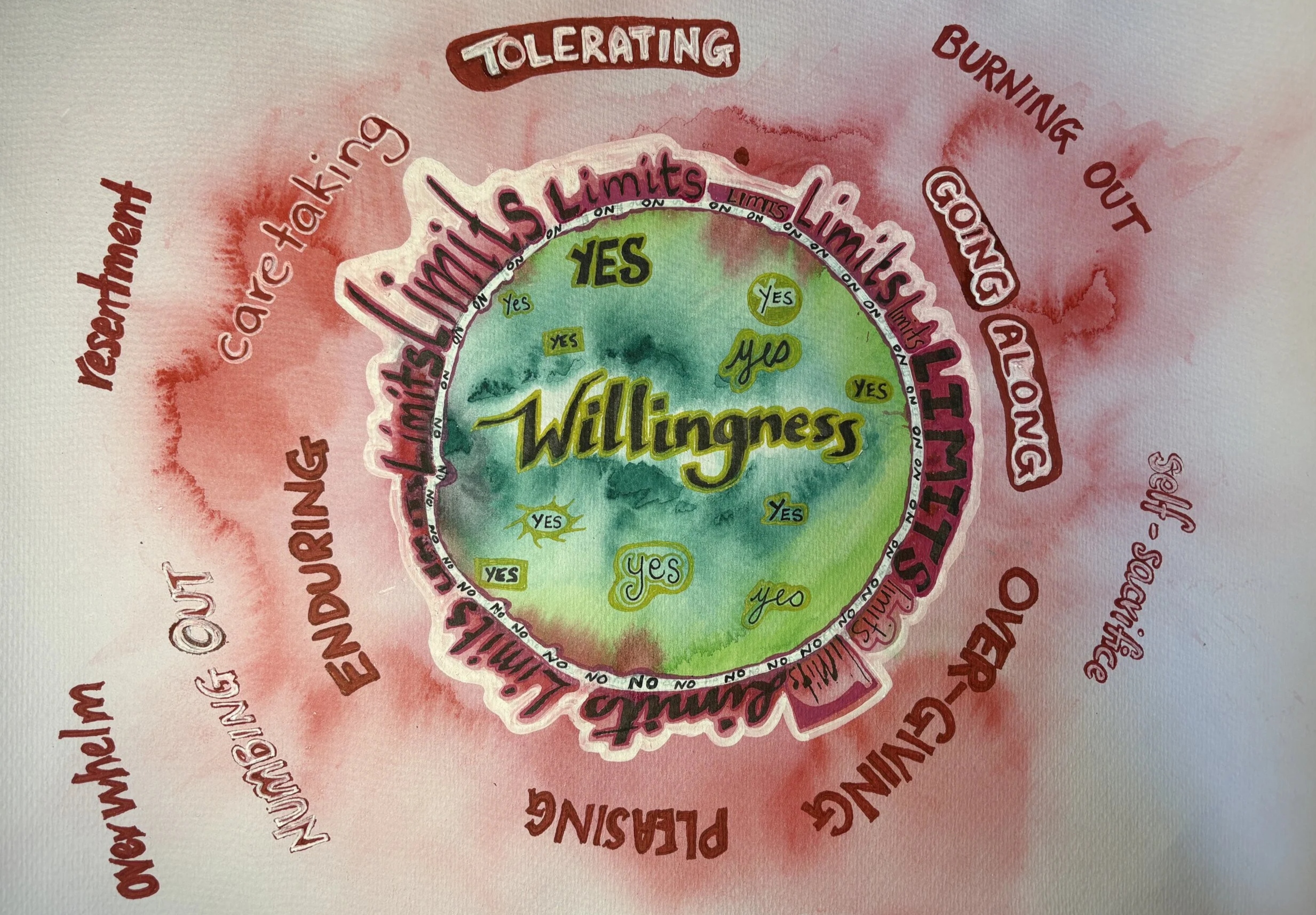

Willingness can feel neutral, calm, or mildly joyful. It can also feel enthusiastic, generously heart-opening, and transcendent. But what truly defines it is your relationship to your no. When you don’t honour your limits, willingness can turn into resentment, overwhelm, or burn-out.

An original artwork by © Vanessa K. Vance, Consent Craft.

The skill of willingness is noticing, trusting, and valuing your no as a feeling and sensation in your body and communicating your limits; what you are willing and not willing to do or allow.

Creating Consent Together

When you honour and communicate your limits, you make space for choice for the person making the request.

This is respect.

The receiver can then decide whether the thing they want can work within those limits.

If it’s a yes, then you’ve created consent together. You’ve found the place where one person’s want can be met by other persons’ willingness and a gift can be given and received.

Both people can feel good about the interaction because they have both know what choice theirs is to make and feel free enough to make a choice that is right for them.

You might then want to take turns giving and receiving so you can both get what you want, and you can both give within your limits.

Consent isn’t always about wanting the same thing. While it’s not impossible, it’s actually quite rare for two people to deeply want the exact same thing, at the exact same time, for any sustained period. We are moving beings. Our wants and desires change moment to moment, influenced by many internal and external factors.

With practice, two way touch interactions can be experienced as an organic fluid dance of giving and receiving.

Why This Matters

Knowing whether you are wanting or willing helps you take responsibility for yourself while respecting the other person’s autonomy.

It allows:

cleaner requests

clearer limits

less resentment

more choice

deeper trust

It can lead to everyone getting more of what they want, while playing within their limits together.

Consent is not just about getting to yes. It’s about creating conditions where giving and receiving can actually feel good in the body, over time, and in relationship. When wanting and willing are named clearly, consent shifts from a transaction into a shared, relational, and embodied practice.

Recommended Resources:

Baczynski, M., & Scott, E. (2022). Creating consent culture: A handbook for educators. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Martin, B. (2021). The art of receiving and giving: The wheel of consent. Luminare Press.

Practising Wanting and Willing

If you’d like to explore wanting and willing through lived, embodied practice, you’re warmly invited to attend a Consent Craft workshop. These distinctions come alive when they’re felt, not just understood.